Book of Earlier Work

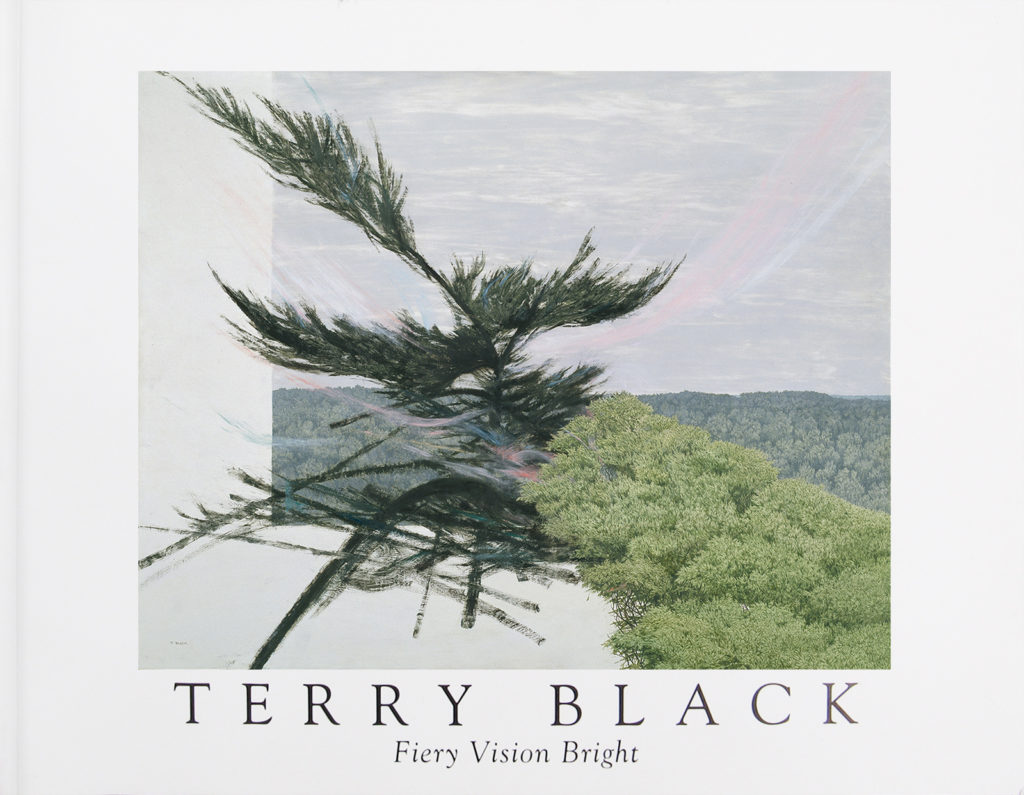

TERRY BLACK Fiery Vision Bright.

Essay by Laurel Gasque, Art historian, Washington.

1995, ISBN 1-57383-0-44-5.

Terry Black (Neil Terence Black) Toronto born Canadian Artist.

Paintings owned by collections on four continents.

(Out of print)

On-line edit.

It’s easy to describe the leaves in Autumn and it’s oh so easy in the spring,

But down through January and February it’s a very different thing . . .

Didn’t I come to bring you a sense of wonder,

Didn’t I come to lift your fiery vision bright,

Didn’t I come to bring you a sense of wonder in the flame. *

Written by Van Morrison,

taken from “A Sense of Wonder” @1984 Caledonia Publications Inc.

All rights reserved, International copyright secured, used by permission.

At a time when artist and audience are not always confident they have common cultural ground to stand on and share, it is reassuring to know of Terry Black’s commitment to communication in his work. That doesn’t mean, however, that he makes his work easy for his viewers; in many ways it is the very opposite. He often makes earnest demands upon them. This implies, however, a serious respect for the viewer and the viewer’s willingness to participate imaginatively in his work.

Perhaps all of the expressive elements of Black’s work are best summed up with stunning technical economy and elegance in his painting of a single wind whipped and weathered pine placed boldly in the absolute foreground of an expansive forested landscape. With great gestural strength reminding one of the work of Franz Kline or the calligraphic quality of Robert Motherwell’s gesturalism, Black breaks the boundaries of location and signs across the surface of the painting a tormented tree that feels like a great Chinese character written with nature’s ink. The precise place of the pine is indefinite. Which world does it belong to? A high slope in the landscape or in the portion of the painting yet to be? Its outstretched branches embrace every significant sector of the painting, spreading above and beyond, yet centred in intimate wisps of colour.

“Paint is really only multi-coloured blood”

Again we find, as the artist tells us, that fomenting below the surface of the painting and inspiring its forms are scriptural subjects such as Jacob striving with men and God and wrestling with an angel (Genesis 2) until he received a blessing as well as the depth of remorse and desire for true worship that David expresses in his great penitential poem (Psalm 51). In the ravaged root of pine one senses the surrogate presence of the artist clinging tenaciously and expectantly. Someone said that writing is easy: you just take a blank piece of paper and open a vein. That Black pours self and soul into paint becomes explicit when he wryly comments, “Paint is really only multi-coloured blood.”

While Black’s work is rooted in the environment he knows best, it is not an expression of reductive regionalism or a matter of descriptive realism that can be accessible only to a viewer who might be familiar with the bucolic beauty of south-central Ontario, Canada. Particularity of place is not an end in itself, but rather a point of departure for broader and more universal themes and reflections that flow implicitly from a specific context.

Confirmation of this was clear in the reception his works received in the very different cultural climate and location of Russia when they were shown there in 1992 at the Palace of Beloselsky, formerly the Communist Party headquarters in Saint Petersburg for seven decades. The Russians didn’t need an interpreter in order to understand the work. They grasped directly the human and aesthetic elements.

For example, Black describes his experience of the Russians’ response to his Balance Owing:

“It is a very formal painting… and it was fascinating for me to see how it was received. They grabbed it instantly. They were nodding in understanding long before the translator said anything to them. Compositionally, you have a triangle within a triangle. The black shape and the white shape are the same size, but one is inverted. There is symbolic balance between the cultivated world and the animal world, the wild world of the woods and forests beyond.”

Pinning labels such as realist or landscapist on Black has pitfalls. The composition of a painting like Balance Owing will rarely be observed, let alone be experience so perfectly in nature. And yet there is great fidelity to nature in this picture. Clearly his work does not fall strictly into tidy realist or landscape painting categories. While the visual grammar and vocabulary of realism undergird his painting, it also exhibits many abstract, formal, and symbolic properties.

Terry Black has been reading two great texts for most of his life. These two texts also happen to be the two greatest texts that Judeo-Christian theologians have ever and always considered worth contemplating.

The first is the Book of God’s World, where we can see the world of nature rather than solely the world of humanity. The second book is the Book of God’s Word, the Holy Scripture, where we can look for the source and meaning of life.

Black’s love for reading both of these books has been integrally formative for the vision that we find presented in his works in this exhibition. As the paintings on view move dramatically from taut realism to a burgeoning expressiveness, from articulate prose to ardent poetry as it were, the underlying spring welling up and watering them is still the wedding of words and worlds from these two great texts.

Even before Terry Black was conventionally literate, he was carefully reading the book of God’s World. Although he was born in Toronto, his childhood memories of it are faint because he moved with his family when he was only two years old to the woods on the Oak Ridges Moraine, Ontario. His first visual vocabulary and reader were the woods, where as a boy he was free to roam and explore in a setting that he then felt went on forever.

Black relates the agony it was for him to be abruptly ripped one day from his first home in the woods to a home on open farm land. Intense personal bonding to place has not only been a life-long experience for him, but, as we shall see, a veritable characteristic of his work.

Black is firm about place. “I can only paint what I know. I couldn’t go to the West Coast and paint. It’s a different visual accent. I don’t feel at home there. You have to work with what you know. I’m not a prairie boy. I don’t feel comfortable by the sea and I don’t know the mountains, but I do know the land and woods of southern Ontario.”

Terry Black has had to struggle though to achieve the sense of confidence he has today in the significance of his rootedness.

Growing up in Ontario, at first I thought the woods were the whole world. When I got a bit older, and started to read, I realized to my chagrin that I lived nowhere. I lived in a very unimportant place on the planet. There had been, I thought, no important literature written here. It all had to do with the UK. And, then later, the States. There was never a mention of Canada, let alone Southern Ontario. No one knew where it was.

“Canada is nowhere I thought. What an embarrassment to come from a place that is nowhere. It was only after time that I came to a point where I felt comfortable with my home. I realized that when you deal with something specific and focused, you can say something that carries a broader truth.”

An indication of the communication he seeks and the effort he calls for from the viewer is reflected in the terribly important part titles play in his earlier work. Meaning is not made explicit or foisted upon us, but is suggested by a dynamic collision between the verbal and the visual.

1989 Oil on masonite 26 X 44 cm

Private collection, Canada

1988 Oil on masonite 32 X 49 cm

Collection of Christopher Cushing, Canada

1989 Oil on masonite 56.5 X 64 cm

Collection of Merchant Private Trust Company, Canada

1988 Oil on masonite 56 X 104 cm

Collection of Connor, Clark & Company Ltd., Canada

We already encountered this in Balance Owing and Steady March, but it is also evident, for instance, in Above the River, where there is no indication that a river is present in the painting. That a river flows beneath the empty bench on the high bluff and that someone might have possibly climbed down to the stream must be deduced. Black alerts us to his intention and gives clear guidance when he says, “The title… [often] encourages the viewer to deal with something that is not in the picture. I like the idea of a picture being bigger than what I’ve been able to fit in the painting.” He also says, “I want my viewers to touch my paintings in some way.”

Black’s later work, as we shall see, goes beyond word play, however, to achieve this “bigger picture” visually by means of energetic and expressive stylistic transformations and strategies.

It’s like setting birds to flight in their imagination.

Black’s respect for his audience doesn’t mean he wants to make us comfortable.

“I hope to disturb, but not alienate, like setting birds to flight in the imagination. Throw a rock at some pigeons on the ground and they’ll take off, swooping and winding and diving, in formation putting on the most gorgeous air show. When birds take flight we really know what they’re all about.”

As one surveys the development of Terry Black’s painting, two pictures in particular stand out as watershed works. They are Private Practice and Devices and Desires. Straddling before and after the 1992 show in Russia, they function back to back in a true visual sense. Out of a decade of complete absence of the human figure in his painting, as if from nowhere, a bold figure appears unaccountably and unavoidably at the immediate foreground of the picture plane of each of these paintings. A real rock hits and scatters the birds of imagination referred to above.

In Private Practice, a person in a scarlet parka, dramatically set off by a white wintry landscape, powerfully pulls back and takes steady aim with a longbow at some target, presumably in the distance, that is completely obscured for the viewer because the back of the figure dominates and totally blocks out access to the line of sight in front of the figure. Inseparably sealed to the landscape in its forward gaze, the figure forms a potent surrogate for the subjectivity of both the artist and the audience to identify with. The hope of this painting lies literally in the openness of its horizon and the piercing point the top of the bow makes vertically into the realm above.

When we move to Devices and Desires, it’s almost as though the figure in Private Practice shed its toque and anorak, donned a hard hat and turned around to confront us. What in the world is happening here? Although the figure now faces us, we still encounter a persona with no face. Staring at us instead is the oculus of a theodolite, a sophisticated computerized surveying instrument used to measure and plot topography, perched on top of a tripod. Behind the tripod the figure steadies the equipment and presumably focuses it with full attention on the viewer. More disconcerting elements emerge.

Why is the figure standing in the middle of the road? What if a car should zoom over the hill behind the figure and miss seeing the sign to the left of the figure and not be able to stop? Why is the sign on the near side of the incline of the hill instead of the far side where it could give earlier warning? Why does the figure wear exotically multi-coloured paint smeared clothing? Is the figure really an artist? Is it a self-portrait?

Furthermore, the title perplexes and entices us with its snippet from the general confession from The Book of Common Prayer: “We have followed too much the devices and desires of our own hearts.” Suddenly the eye of the theodolite becomes less casual and accidental and more probing with assessment and meaning. With this painting we also come to a completion of the representation of the constructed and contained, of walls and buildings, tools and toys, high tech roads and instruments set in nature. The moment of measuring, “the measure of all things,” has been approached by the counterpoise between being the observer and being observed.

Next we see an explosive energy entering Black’s painting. Titles fall away. Boundaries are burst. A freer gestural style flows sometimes on or beyond a tauter style and technique and even threatens to displace it.

One feels Black moving from seeing with the eye to seeing through the eye. Windswept wild pine wrestle and soar to the limits of the frame and into unfinished portions of the painting to suggest worlds within worlds and dimensions beyond. Sumac surge along a stream of Vermilion. Thin leafless trees sway with palpable vulnerability.

There was a significant change in Black’s work after he spent some time in Russia. This is how he describes the change:

“The newer work was starting to happen a lot faster. It was more intuitive. At times I was using larger and larger brushes, but for some things no brush I used would work. I just had to throw down the brushes and plunge my hands into the paint and start smearing it around. I was painting with my fingers. I realized I was painting with the “tools” I used as a five year old! Very immediate. Primal. It had an electricity and force to it that I couldn’t get any other way.

The thing is, I’m often working over wet paint and can easily destroy the whole thing. After putting in a tremendous amount of work, you have to be prepared right up until the last few minutes to destroy the whole painting. And it has happened. You have to be prepared to dare and stay loose.”

Although Black has forsaken titles for most of his work, he hasn’t failed to find themes for them. He is passionately articulate about their underlying inspiration.

1993 Oil on masonite 88.5 X 91.5 cm

Collection of Jonathan Spaetzel, Canada

1987 Oil on masonite 31 X 52 cm

Collection of John C. Clark, Canada

1984 Oil on masonite 39.5 X 60 cm

Collection of Caldwell Securities Ltd., Canada

Circa 1999 Oil on masonite

Private collection, Canada

In reflecting on Terry Black’s painting, his love of reading the two great texts of the Book of God’s World and the Book of God’s Word has been evident throughout.

After tracing the scope of his works and seeing in them the emergence of a new dynamism from a dearly earned discipline, it is even more clear that these books have been integrally formative for the vision that we find expressed in the paintings in this exhibition.

Black says he always wants to paint something that’s open; something that would allow us in.

We believe he has.

The quotations in the above text were based on interviews with Terry Black in Toronto in March and April 1995.

Laurel Gasque is a cultural historian and writer who lives in Washington. She has taught at Regent College (Vancouver), New College Berkley (California), and Eastern College (Philadelphia). She has published numerous articles, including essays on Paul Gauguin, Gathie Falk, and Eric Gill and on such subjects as Russian icons, the spiritual in art. She also gives seminars on the strategic importance of art in education.